Olivia L. Thomas

International Journal of Maritime History. Volume 36, Issue 1, February 2024 Pages 107-139

https://doi.org/10.1177/08438714231198614

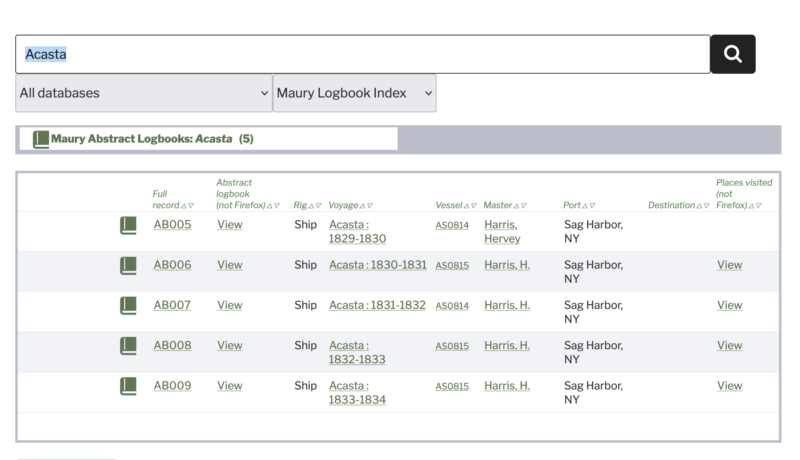

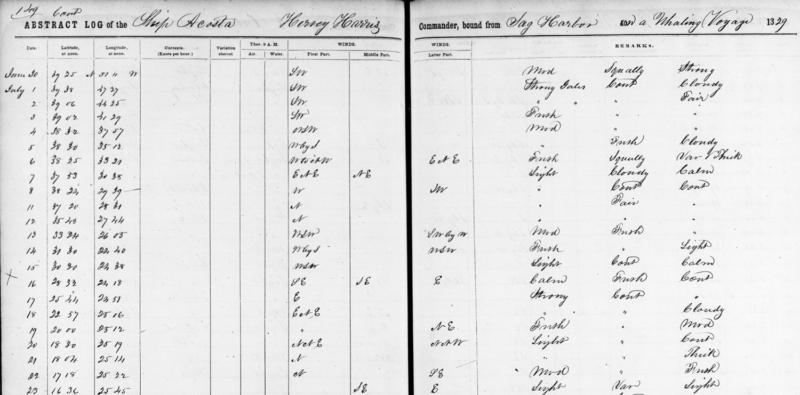

Index to newly-scanned Maury Abstract Logbooks

Dale Chatwin’s index to the scanned Maury Abstract Logbooks is now available on whalinghistory.org. The original source material consists of almost one hundred volumes of handwritten abstracts of logbooks from voyages of American (and a few other) vessels from 1796 to 1861. Among them are at least 650 whaling voyages. The entries contain information about position, wind, weather, and whales captured or seen abstracted from the original logbooks. They are one of the data sources for the American Offshore Whaling Logbook database and the maps on whalinghistory.org. (The transcriptions were done by Tim Smith’s CoML group in the 1990s.)

The abstracts were compiled by the then-new U. S. Naval Observatory before the Civil War, which published maps of where the whales were to aid whalers. The original volumes are held by the National Archives and Records Administration, which recently scanned everything and made it available on the Internet. https://catalog.archives.gov/id/597822

Early this summer Dale Chatwin compiled an index that connects each whaling voyage in the abstracts to the beginning page of its entry in the Maury abstracts, with a URL for that page in the scanned version.

Also, for many voyages there are lists of the major ports of call during the voyage, with dates and travel times. These are linked as “Places visited”. For example, https://catalog.archives.gov/id/454830299?objectPage=247*

To find links to the index and to places visited:

- Search for a vessel, voyage, master or year in the main search box on any page. Maury index records linked to those search terms will come up in their own results tab. For instance, search ‘Thorn 1835’ (no quotation marks). You’ll get results for 2 voyages, 2 voyage maps and 2 Maury abstract logbooks for the 1835 voyages of the ship Thorn. (And 2 other voyages and 2 Dennis Wood abstracts for 1835 voyages owned by G. R. Thornton!)

- Or, choose Maury Abstract Logbook Index from the Explore menu in the heading on any page. This will return all 649 current entries. You can then use the search box to search within the index entries.

- Or, use the rightmost dropdown menu beside the search box to limit your search to ‘Maury Logbook Index’.

* Please be aware that none of the links to NARA’s scans of the abstracts will work properly if using the Firefox browser. NARA’s scan viewer and Firefox’s javascript interpreter don’t see eye to eye.

New database: Australian Colonial Whaling Ship Voyages

We are pleased to announce the availability of a database of Australian Colonial Whaling Ship Voyages from 1805 through 1898. The database lists the voyages made by the whaling vessels that were owned, registered or based in Australian ports. A few British whalers are also included, some due to the fact they were temporarily based in an Australian port and others because they were owned, or part-owned, by Australian residents although registered and based in Britain.

The database was built from six lists compiled by Mark Howard—The voyages; The fleet; The owners; The captains; The crewmen; and Where the Australian Whalers Went.

British Southern whaling database updated, January 2025

The British Southern Whale Fishery voyage and crew datasets have been updated with 900 amended or new whale oil cargo entries. This represents almost one-third of all known British Southern voyages. The updates have been sourced from the ledgers of the London Gauger held at the London Metropolitan Archives. A Working Paper describing the nature of the Gauger’s records and related matters is available (see sidebar). The new data was extracted with the support of the International Whaling Commission (IWC) and will hopefully assist in developing estimates for the historical population of the southern right whale.

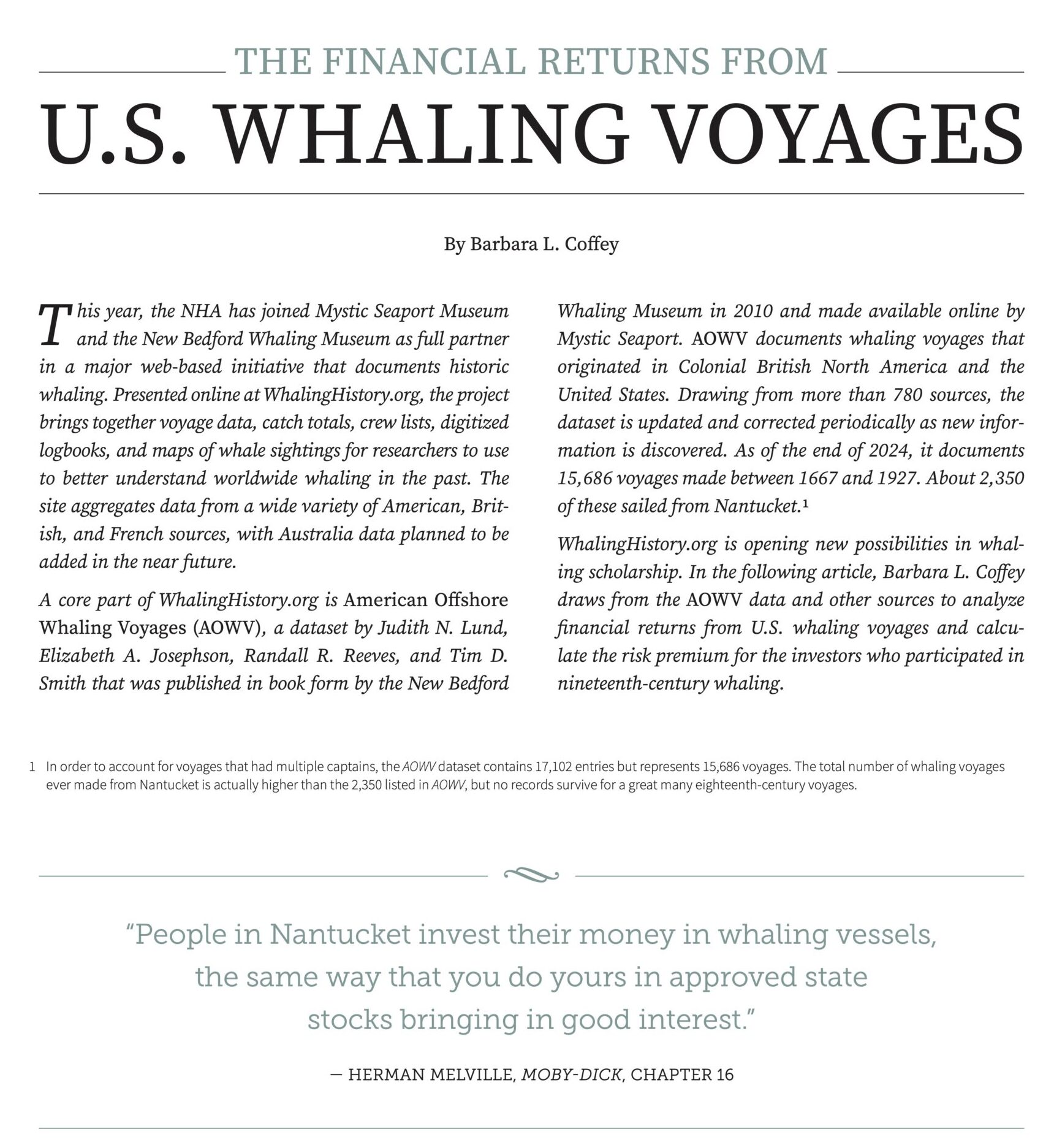

Financial Returns From U.S. Whaling Voyages

Barbara L. Coffey

Historic Nantucket, late Fall 2024, Volume 74, No. 3

Nantucket Historical Association

Download article →

Barbara L. Coffey is a librarian at Monmouth University. Previously, she was a research analyst on Wall Street.

American, Scottish Arctic and British Southern whaling data updated

The American Offshore Whaling databases have been updated for 2024, to include more 18th century voyages and wives of whaling masters as well as many corrections and updates to existing voyage entries. Updates to the crew list database include more than 160 New Bedford crew lists and several hundred lists from the records of whaling owners and agents Aiken & Swift.

The Scottish Arctic Whaling database has been revised and corrected.

The British Southern Whale Fishery databases have been revised and updated with additional voyages, crew lists, and data corrections.

Just search

If you’re not sure where to begin, use the Search box in the banner at the top of any page. Enter a person’s name, a vessel name, a year, or any other words of interest and click the ‘magnifying glass’ icon. This site Search function knows about all of the databases and all of the web pages on the Whaling History website. It will return any results it finds from each one in a separate tab.

Information about using the Search function will appear below your search results. View the Search documentation here → (when you get there, click on the “View search help” button.)

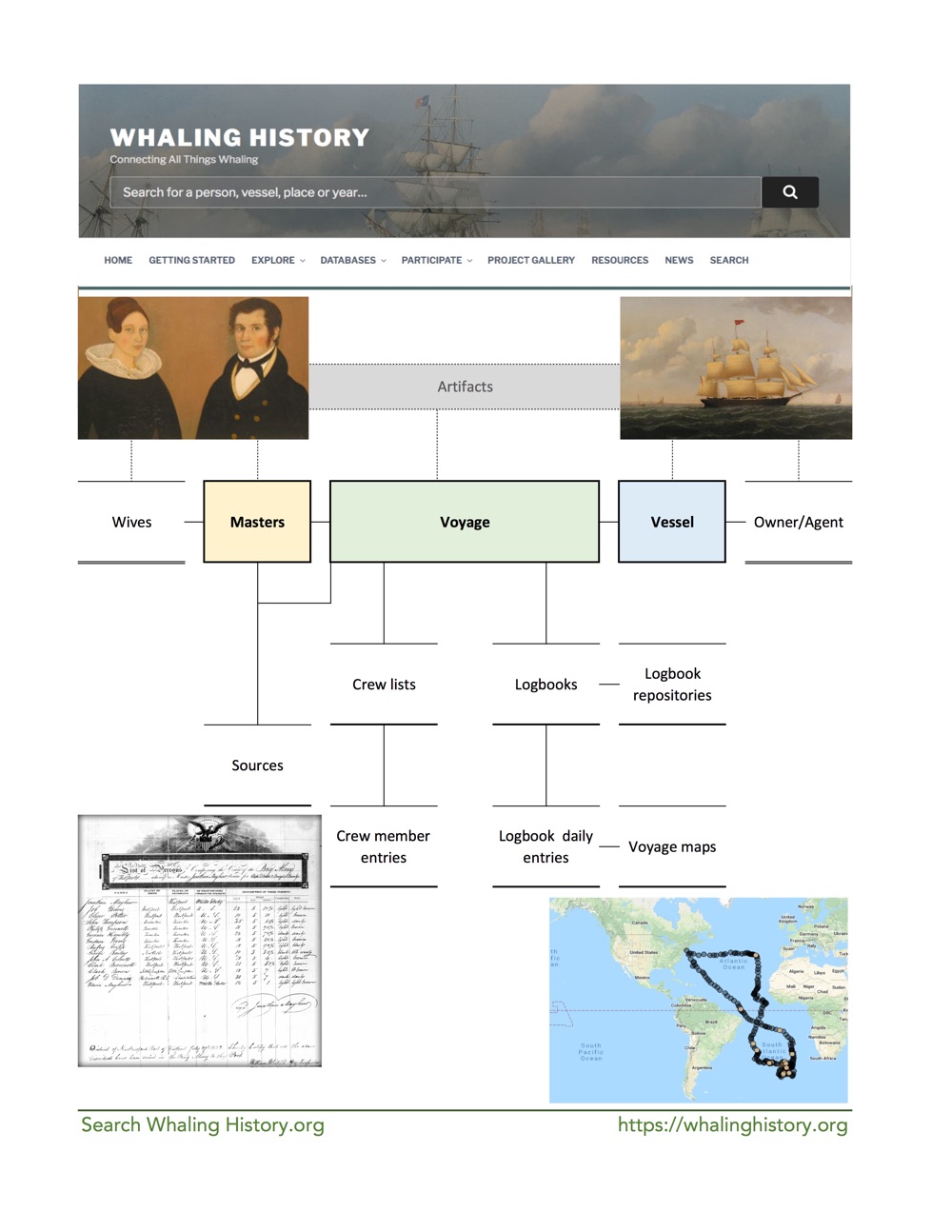

Data map

The data map below shows the entities represented in the databases and the main connections among them to help you visualize what is going on in your search results. Click on the data map to view or print a PDF version.

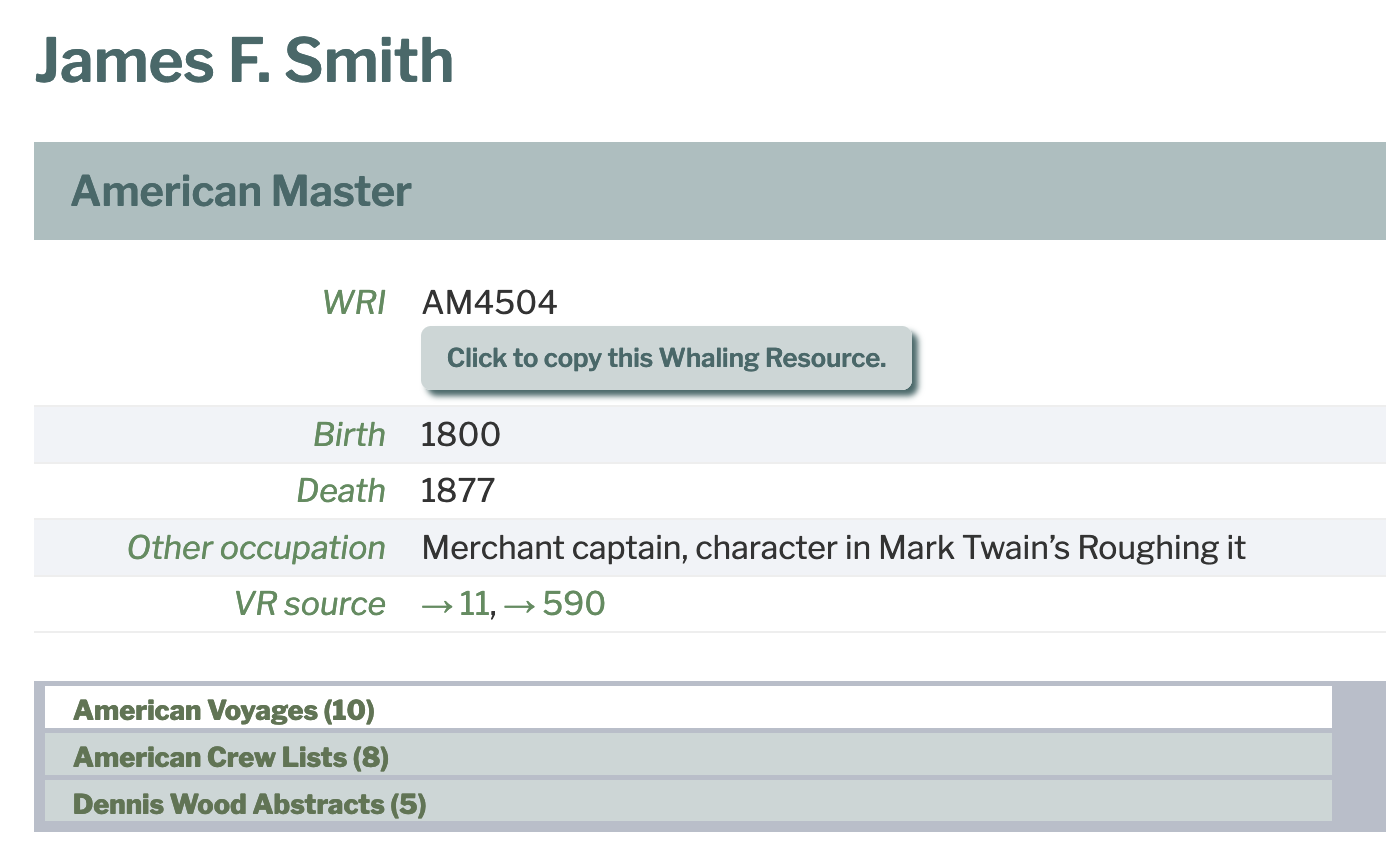

Whaling Resource Identifiers

Every entity record in the WhalingHistory.org databases has a unique Whaling Resource Identifier (WRI). Just as libraries assign each book a call number and museums refer to an object in their collection by an accession number, you can cite a whaling master, vessel, voyage, crew list, etc. from WhalingHistory.org by its WRI. Even better, the long form of that WRI can be used as a URL, enabling anyone anywhere on the Internet to link directly to that record.

Every entity record in the WhalingHistory.org databases has a unique Whaling Resource Identifier (WRI). Just as libraries assign each book a call number and museums refer to an object in their collection by an accession number, you can cite a whaling master, vessel, voyage, crew list, etc. from WhalingHistory.org by its WRI. Even better, the long form of that WRI can be used as a URL, enabling anyone anywhere on the Internet to link directly to that record.

- The short form of a WRI consists of two letters (which identify the database and record type) followed by a string of digits. For example, James F. Smith’s short WRI is “AM4504”

- The full form of that WRI adds “https://whalinghistory.org/wri/” before the short WRI to get https://whalinghistory.org/wri/AM4504

- You can find and copy the full WRI for an entity by going to its page in WhalingHistory.org and choosing “Click to copy this Whaling Resource.”

A WRI provides a unique permalink to any record in the databases. This allows us to:

- Refer to a record unambiguously when discussing it or making corrections

- Enrich catalog records with links to WhalingHistory.org

- Cite the information in the record

- Share in email, texts and social media

- Link from papers, presentations, exhibits, wall labels, and other databases

- Create QR codes and other gimmicky Internet stunts

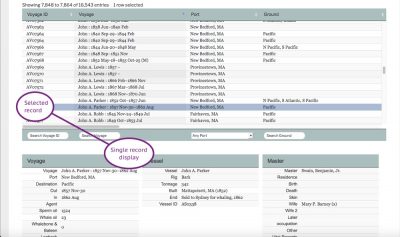

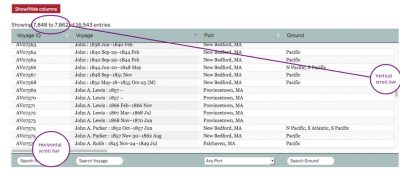

The Data Viewer Interface

When the the main site search is not specific or flexible enough for your needs, use the data viewers. Each database has its own data viewer—a tabular display window to interact with the data—and all of the data viewers share a common set of features.

The data viewers are available from the Databases item on the main menu at the top of every page.

Scrolling

The view displays a scroll bar on the bottom to scroll left-and-right through the available columns. A scroll bar on the right edge scrolls through the records. In the top left, the viewer shows the records currently in the display window. If you have a tablet or other touch screen device, you can also swipe vertically or horizontally to scroll the data.

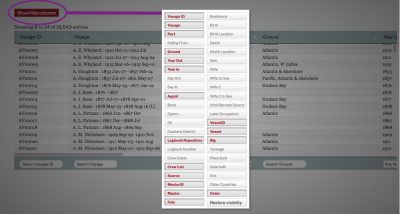

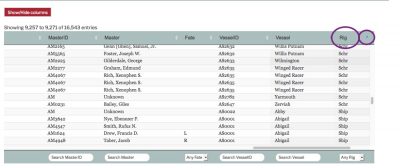

Showing columns

You can choose to hide or show any of the columns in the database. Click the red Show/Hide Columns button in the top left to display all of the column names. Click on a column name to toggle it on or off. Each database has a Columns Definitions page where you can learn more about the content its columns. (Click outside column name box to continue.)

Sorting

Click on any column heading to sort the database by that column. The triangle to the right of that column name will turn blue to indicate that the column is sorted. Click again on the column heading to reverse the sort order. (The blue triangle will invert.) To add more columns to your sort shift-click on their column headings.

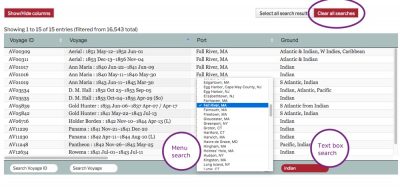

Searching

At the top or bottom of each column is a search box. Some columns have a selection menu that will pop up, others have a free form text box. Text searches are not case sensitive.

Multiple search words are treated as if joined with AND, so choosing “Fall River, MA” with the Port menu and typing “indian” in the Ground search box will result in all voyage records that have Port=”Fall River, MA” AND Ground contains “indian”.

Some of the databases are very large—please be patient, your search results may not appear instantaneously. To clear all active searches, use the red “Clear all searches” button in the top right.

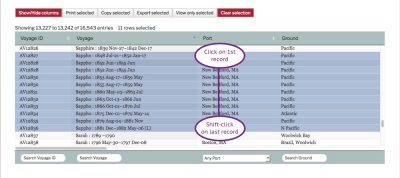

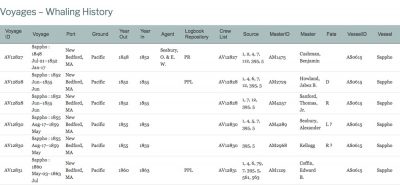

Selecting and displaying one voyage

In the Voyages database, click on a single row in the data viewer for a full display of all aspects of the voyage at the bottom of the page.

Selecting multiple records

To select more than one row, click on the first row, then add more with shift-click. Depending on your browser and operating system, you may also be able to add individual records using ctrl-click or ⌘-click.

To select more than one row, click on the first row, then add more with shift-click. Depending on your browser and operating system, you may also be able to add individual records using ctrl-click or ⌘-click.

Select all search results

Or, after searching the database you can select the found records by clicking the “Select all search results” button that will appear in the top right. To unselect all selected records, click the red “Clear selection” button.

Printing, copying, exporting

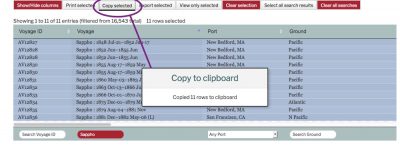

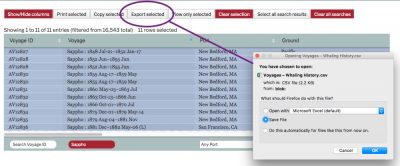

Printing, copying and export all work with a selection, which may include one or more records. For the examples below we’ve selected all the voyages of the bark Sappho. This selection happens to fit neatly in our data viewer window, but your selection might include many more records than you can view at one time.

The set of columns that you’ve chosen with the “Show/Hide” button will be the columns that appear in your print, copy or export.

To produce a printable version of the selected records, click on the “Print selected” button in the top left. A new browser window will open with your data in a table. You can then print the page using your browser’s print command. Depending on your operating system, you may also be able to save the output as a PDF file, or email or text it to yourself and others.

To produce a printable version of the selected records, click on the “Print selected” button in the top left. A new browser window will open with your data in a table. You can then print the page using your browser’s print command. Depending on your operating system, you may also be able to save the output as a PDF file, or email or text it to yourself and others.

Copy

To copy the selected records to your clipboard, click on the “Copy selected” button. A message will appear to tell you that the data has been copied. You can then paste the data into any other application. It is properly formatted so that you can paste directly into a spreadsheet. It will also format neatly in a word processor. If pasted into a plain text editor, the result will be tab-delimited text.

To copy the selected records to your clipboard, click on the “Copy selected” button. A message will appear to tell you that the data has been copied. You can then paste the data into any other application. It is properly formatted so that you can paste directly into a spreadsheet. It will also format neatly in a word processor. If pasted into a plain text editor, the result will be tab-delimited text.

Export

To export your selection as a CSV file, click on the “Export selected” button. Your computer operating system will prompt you to save the data. The resulting file will be comma-delimited and all columns will be wrapped with quotation marks. The first row will contain the column names. A file in this format can be opened in a spreadsheet, or it may be imported into software for managing databases or performing statistical analysis.

Crew Lists: Frequently Asked Questions

Where do crew lists come from?

Crew lists appear in many different primary sources. American crew lists in WhalingHistory.org have usually come from one of these sources:

- Government records kept at U. S. Customs Houses. These can be ‘outbound’ (filed before leaving port) or ‘inbound’ (filed when returning at the end of the voyage.) These official crew lists were required of vessels leaving U. S. ports beginning in 1803. See the Crew Lists About page. These records are official U. S. government records preserved by the U. S. National Archives and Records Administration.

- Articles of Agreement. These constitute the formal contract between the vessel’s owners and each member of the crew. See “Articles of Agreement” in Stein, Douglas L., American Maritime Documents

- Whalemen’s Shipping List and Merchants’ Transcript. This weekly newspaper was published in New Bedford. It printed crew lists of departing vessels in the second half of the 19th century.

- Other newspaper reports.

- Logbooks and journals. Sometimes the keeper of the ship’s logbook or a personal journal would list some or all of the members of the crew.

- Books kept by owners, agents, and shanghaiers, such as the Aiken & Swift Manuscript book, or the San Francisco Shangaiers 1886-1890 database.

How are they different? What information do they contain?

- Outbound crew lists contain:

–The name and rig of the vessel, the name and signature of the master, the destination of the voyage, the date that the crew list was filed.

–And for each crew member: name, birthplace, place of residence, citizenship; sometimes age, height, skin, hair; and rarely other notes.

–They do not include crew members who joined the voyage after its initial departure from port. - Inbound crew lists contain a handwritten copy of the outbound crew list plus additional information:

–The date that the inbound list was filed with the customs house, the name and signature of the master (or other responsible person).

–And a notation accounting for each crew member who did not return with the vessel.

–They sometimes include information about crew members who joined the voyage after its initial departure from port. - Crew lists from Articles of Agreement contain:

–The name and rig of the vessel and the destination of the voyage.

–And for each crew member: signature, date of signing, rank or position, and lay. - Crew lists from the Whalemen’s Shipping List and Merchants’ Transcript usually contain names, places of residence, and ranks.

- Crew lists from logbooks, journals and other documents vary widely but typically include names and ranks for some or all crew members.

- Crew lists from books kept by owners, agents, and shanghaiiers vary widely, always including name, but they may also include rank, lay or pay rate, performance notes, and other information. They may list only officers, or only seaman, or combinations, depending on the purposes of the list keeper.

They often include crew members who joined the voyage after its initial departure from port.

Why is my ancestor’s name spelled wrong?

- Names change over time. Sometimes descendants change the spelling of family names. Sometimes your ancestor didn’t spell his name quite the way you might think. Sometimes he didn’t spell it consistently throughout his life. Sometimes the person who wrote his name down didn’t hear or spell it correctly, this was especially a problem with uncommon and non-English names. Sometimes clerks made mistakes. Sometimes your ancestor couldn’t spell his own name.

- All of the source documents were originally written by hand. Nineteenth-century pens were usually dip pens, often cut from feathers. Some clerks had clear handwriting, some didn’t. Inbound crew lists started with handwritten copies of the handwritten outbound crew list, then the additional information was written in, by hand, crammed into whatever open space was available on the page. The documents have been filed, folded, unfolded, and moved many times over the last hundred to two hundred and fifty years—they have developed creases and holes. Then many of them were were microfilmed. Then the original or the microfilm was scanned digitally. Then one or more people transcribed the information from the scans into digital files, doing the best they could to figure out the original writing. Then those files were loaded into databases, which have been converted several times as technology has changed. Unsurprisingly, there may be errors.

Why is my ancestor missing from the crew list database?

Crew lists were supposed to be filed, but sometimes they weren’t. Sometimes the records were later lost. Official crew lists were intended for the protection of American citizens, so they may not carry as much (or any) information about foreign-born crewmen. And, crew lists, like other primary sources, are snapshots in time—if a crew list was submitted before the beginning of a voyage, it will not contain information about crew members who joined the voyage later.

Why are there duplicate entries?

Sometimes the database contains two copies of the same crew list, usually because the original document was transcribed by different people working on different projects years apart. There are often differences in how they interpreted the original handwriting, which leads to very different spellings for some names. We keep both versions to improve the chance that you find the name you are looking for.

Why are there multiple crew lists for one voyage?

- Often the database contains both the outbound and the inbound crew list for a voyage. These look very similar in the database, but they really are from two different handwritten nineteenth-century documents. Certain entries on one document may be more readable or less damaged than they are on the other, leading to better transcriptions of the information. And, the inbound list has extra information about crew members who did not return.

- Or, there may be two or more crew lists from completely different sources. Again, we provide them all in order to capture as much information as is available, even though they may conflict.

What do the column labels mean?

See the Crew List Column Definitions.

How can I learn more about crew lists?

- About Crew Lists

- “Crew List” in Stein, Douglas L., American Maritime Documents

How can I help improve the data?

If you have relevant information from other sources (public sources, family documents, etc.) or you have found a transcription error, write to us using the Contact form.

Learn about Whaling

WhalingHistory.org is a repository for data about whaling. For a general overview of whaling and whaling history, here are some resources to start your exploration. Each of them takes a different approach: a narrative, a collection of artifacts and maps, a timeline, a collection of topics, a map, a work of literature.

- Yankee Whaling, New Bedford Whaling Museum

- Whaling Resource Sets, Mystic Seaport Museum for Educators

- The History of Whaling in America, PBS American Experience

- Whaling, Smithsonian Institution Museum of American History

- Map of Whaling Grounds, A. Howard Clark (c. 1884)

- Moby-Dick or the Whale, Herman Melville

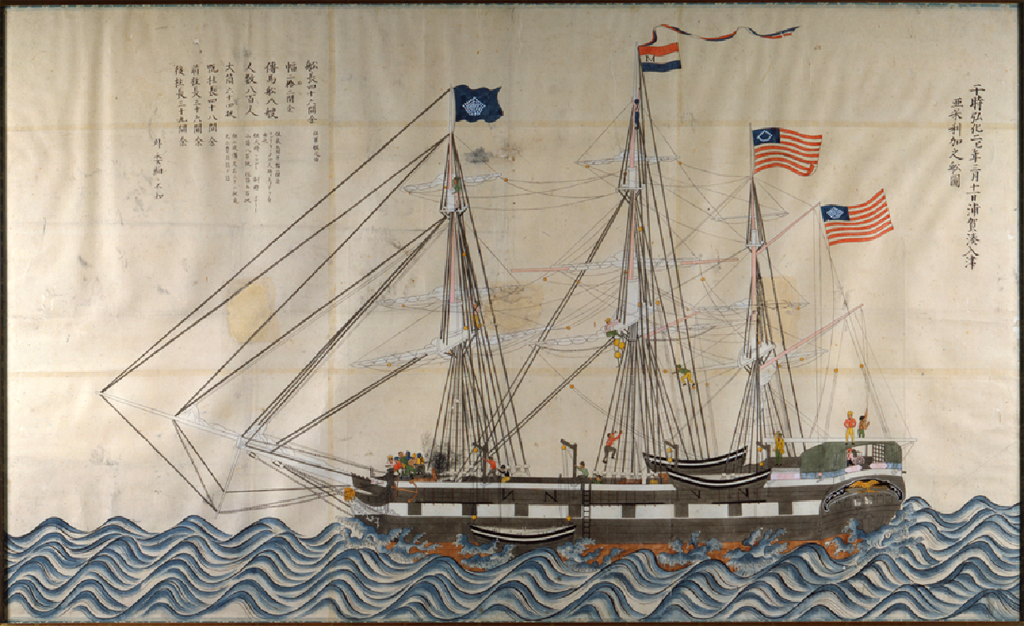

American Whaling Mapped

An animated visualization of Matthew Maury’s collection of data from logbooks of American whaling voyages. From Data narratives and structural histories: Melville, Maury, and American whaling by Ben Schmidt:

“Data visualizations are like narratives: they suggest interpretations, but don’t require them. A good data visualization, in fact, lets you see things the interpreter might have missed. This should make data visualization especially appealing to historians. Much of the historian’s art is turning dull information into compelling narrative; visualization is useful for us because it suggests new ways of making interesting the stories we’ve been telling all along. In particular: data visualization lets us make historical structures immediately accessible in the same way that narratives have let us do so for stories about individual agents.

“I’ve been looking at the ship’s logs that climatologists digitize because it’s a perfect case of forlorn data that might tell a more interesting story. My post on European shipping gives more of the details about how to make movies from ship’s logs, but this time I want to talk about why, using a new set with about a half-century of American vessels sailing around the world.

“To find something I might more usefully be able to discuss, I went through the biggest source of historical shipping records, the ICOADs collection, and pulled out the very first systematic collection of logbooks ever assembled: Matthew Maury’s collection of American shipping from about 1785 to 1860, assembled mostly before the Civil War.”

Scottish Vessels Lost in the Arctic Bowhead Whale Fishery (1750–WWI)

Table

Legend: Hunt** = East Greenland (EG), Davis Strait (DS), Newfoundland (NL), Cumberland Gulf (CG)

Note: For additional data, see Scottish Arctic Whaling. In the table below, click on a column heading to sort by that column. Click on an entry in the “Link to Whaling History” column to view voyage data for that vessel.

| Lost | Vessel | Sail/ Steam | Link to Whaling History | Port | Hunt** | Years Whaling | Total Seasons |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1751 | Hopeton | s | SS127 | Edinburgh | EG | 1751 | 1 |

| 1756 | Thistle | s | SS264 | Borrowstounness | EG | 1752-6 | 5 |

| 1757 | Prince of Wales | s | SS211 | Edinburgh | EG | 1753-7 | 5 |

| 1758 | Borrowstounness | s | SS035 | Borrowstounness | EG | 1755-8 | 4 |

| 1762 | Hawke | s | SS116 | Anstruther | EG | 1758-62 | 5 |

| 1763 | Edinburgh | s | SS078 | Edinburgh | EG | 1752-63 | 12 |

| 1775 | Oswald | s | SS193 | Borrowstounness | EG | 1755-75 | 21 |

| 1775 | Peggy | s | SS199 | Borrowstounness | EG | 1752-75 | 23 |

| 1777 | Royal Bounty (1) | s | SS235 | Edinburgh | EG | 1752-77 | 26 |

| 1778 | Campbelton | s | SS042 | Edinburgh | EG | 1751-78 | 28 |

| 1782 | Dundee (1) | s | SS068 | Dundee | EG | 1754-82 | 29 |

| 1791 | Neptune | s | SS185 | Edinburgh | EG | 1787-91 | 5 |

| 1792 | Montrose | s | SS181 | Montrose | DS | 1787-92 | 6 |

| 1792 | Princess of Wales (1) | s | SS215 | Dunbar | EG | 1759-92 | 33 |

| 1798 | Blessed Endeavour | s | SS031 | Dunbar | EG | 1753-98 | 44 |

| 1799 | Toy(1) | s | SS259 | Dundee | EG | 1786-99 | 14 |

| 1804 | East Lothian | s | SS074 | Dunbar | EG | 1785-1804 | 19 |

| 1806 | Simms | s | SS240 | Edinburgh | EG | 1805-6 | 2 |

| 1808 | North Star | s | SS189 | Borrowstounness | DS | 1799-1808 | 8 |

| 1813 | Latona | s | SS160 | Aberdeen | EG | 1785-1813 | 29 |

| 1813 | Oscar | s | SS192 | Aberdeen | EG | 1812-13 | 2 |

| 1816 | Earl of Fife | s | SS071 | Banff | EG | 1814-16 | 3 |

| 1818 | Elbe | s | SS080 | Aberdeen | DS | 1812-18 | 7 |

| 1819 | Diamond | s | SS060 | Aberdeen | EG | 1812-19 | 8 |

| 1819 | Mary Ann | s | SS174 | Dundee | DS | 1803-19 | 17 |

| 1819 | Raith | s | SS220 | Edinburgh | DS | 1785-1819 | 35 |

| 1819 | Royal Bounty (2) | s | SS236 | Edinburgh | DS | 1785-1819 | 35 |

| 1819 | Sisters | s | SS243 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1818-19 | 2 |

| 1819 | Thomas and Ann | s | SS269 | Edinburgh | DS | 1805-19 | 15 |

| 1819 | Toy(2) | s | SS260 | Dundee | DS | 1813-19 | 7 |

| 1821 | Dexterity | s | SS058 | Edinburgh | DS | 1812-21 | 10 |

| 1821 | Elizabeth | s | SS084 | Aberdeen | DS | 1813-21 | 9 |

| 1821 | Larkins | s | SS058 | Edinburgh | DS | 1813-21 | 9 |

| 1822 | Calypso | s | SS041 | Dundee | DS | 1810-22 | 13 |

| 1822 | Hero | s | SS122 | Montrose | DS | 1820-22 | 3 |

| 1822 | Invincible | s | SS131 | Peterhead | DS | 1819-22 | 4 |

| 1825 | Don | s | SS064 | Aberdeen | DS | 1814-25 | 12 |

| 1825 | Estridge | s | SS096 | Dundee | DS | 1800-25 | 26 |

| 1825 | Success | s | SS255 | Edinburgh | DS | 1805-25 | 21 |

| 1826 | Jean | s | SS145 | Peterhead | EG | 1818-26 | 9 |

| 1828 | Active | s | SS004 | Peterhead | DS | 1810-28 | 19 |

| 1828 | Alpheus | s | SS021 | Peterhead | DS | 1818-28 | 11 |

| 1828 | Enterprize (1) | s | SS090 | Peterhead | DS | 1824-8 | 5 |

| 1829 | Home Castle | s | SS124 | Edinburgh | DS | 1813-29 | 17 |

| 1829 | Jane | s | SS138 | Aberdeen | DS | 1801-29 | 29 |

| 1830 | Achilles | s | SS003 | Dundee | DS | 1820-30 | 11 |

| 1830 | Alexander (1) | s | SS014 | Aberdeen | DS | 1819-30 | 12 |

| 1830 | Baffin | s | SS028 | Edinburgh | DS | 1825-30 | 6 |

| 1830 | Hope | s | SS125 | Peterhead | DS | 1802-30 | 29 |

| 1830 | John | s | SS146 | Greenock | DS | 1811-30 | 29 |

| 1830 | Letita | s | SS157 | Aberdeen | DS | 1812-30 | 19 |

| 1830 | Middleton (1) | s | SS177 | Aberdeen | DS | 1812-30 | 19 |

| 1830 | Princess of Wales (2) | s | SS216 | Aberdeen | DS | 1813-30 | 18 |

| 1830 | Rattler | s | SS224 | Edinburgh | DS | 1803-30 | 28 |

| 1830 | Resolution (1) | s | SS229 | Peterhead | DS | 1813-30 | 18 |

| 1830 | Spencer | s | SS248 | Montrose | DS | 1815-30 | 16 |

| 1830 | Three Brothers | s | SS270 | Dundee | DS | 1813-30 | 18 |

| 1831 | James | s | SS134 | Peterhead | DS | 1829-31 | 3 |

| 1831 | Rambler | s | SS221 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1820-31 | 12 |

| 1832 | Eggington | s | SS079 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1830-2 | 3 |

| 1832 | Juno | s | SS149 | Edinburgh | DS | 1813-32 | 20 |

| 1832 | William Young | s | SS288 | Edinburgh | DS | 1831-2 | 2 |

| 1834 | London | s | SS164 | Montrose | DS | 1813-34 | 22 |

| 1835 | Middleton (2) | s | SS178 | Aberdeen | DS | 1813-35 | 23 |

| 1836 | Thomas | s | SS267 | Dundee | DS | 1823-36 | 14 |

| 1840 | Heda | s | SS117 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1834-40 | 7 |

| 1840 | Perseverance | s | SS200 | Peterhead | EG | 1811-40 | 29 |

| 1847 | Alfred | s | SS018 | Borrowstounness | DS | 1836-47 | 10 |

| 1847 | Caledonia | s | SS040 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1821-47 | 27 |

| 1849 | Mary | s | SS172 | Aberdeen | EG | 1838-49 | 12 |

| 1849 | Superior | s | SS256 | Peterhead | DS | 1815-49 | 33 |

| 1852 | Horn | s | SS128 | Dundee | DS | 1805-52 | 45 |

| 1852 | Joseph Green | s | SS147 | Peterhead | EG | 1831-52 | 21 |

| 1852 | Regalia | s | SS226 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1835-52 | 13 |

| 1852 | Spitzbergen | s | SS249 | Peterhead | EG | 1852 | 1 |

| 1854 | Felix | s | SS099 | Banff | EG | 1852-4 | 3 |

| 1856 | Princess Charlotte | s | SS212 | Dundee | DS | 1820-56 | 37 |

| 1857 | Gypsy | s | SSI 13 | Peterhead | DS | 1855-7 | 3 |

| 1858 | Eclipse | s | SS076 | Peterhead | DS | 1820-58 | 39 |

| 1858 | Heroine | s | SSI 20 | Dundee | DS | 1833-58 | 11 |

| 1858 | Jackal | st | SS133 | Peterhead | CG | 1857-8 | 2 |

| 1858 | Traveller | s | SS271 | Peterhead | CG | 1821-58 | 37 |

| 1859 | Advice | s | SS007 | Dundee | DS | 1805-59 | 51 |

| 1859 | Empress of India | st | SS087 | Peterhead | EG | 1859 | 1 |

| 1859 | Innuit | st | SS129 | Peterhead | EG | 1857-9 | 3 |

| 1859 | Union | s | SS280 | Peterhead | CG | 1813-59 | 44 |

| 1860 | Enterprize (2) | s | SS091 | Fraserburgh | EG | 1845-60 | 16 |

| 1860 | Fairy | s | SS098 | Peterhead | EG | 1820-60 | 34 |

| 1861 | Commerce | s | SS054 | Peterhead | DS | 1828-61 | 34 |

| 1861 | St. Andrew | s | SS250 | Aberdeen | DS | 1813-61 | 42 |

| 1862 | Abram | s | SS002 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1855-62 | 8 |

| 1862 | Alexander (2) | s | SS015 | Dundee | DS | 1831-62 | 32 |

| 1862 | Arctic (1) | s | SS023 | Aberdeen | CG | 1856-62 | 7 |

| 1862 | Chieftain (1) | s | SS045 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1833-62 | 30 |

| 1862 | Lord Gambier | s | SS165 | Kirkcaldy | DS | 1853-62 | 10 |

| 1862 | Resolution (2) | s | SS229 | Peterhead | DS | 1830-62 | 33 |

| 1863 | Dundee (2) | st | SS070 | Dundee | DS | 1859-63 | 5 |

| 1863 | Jumna | st | SS148 | Dundee | DS | 1857-63 | 7 |

| 1864 | Emma | st | SS086 | Dundee | EG | 1863-4 | 2 |

| 1866 | Dublin | s | SS067 | Peterhead | CG | 1846-66 | 21 |

| 1868 | Columbia | s | SS052 | Dundee | DS | 1851-68 | 17 |

| 1868 | River Tay | st | SS231 | Dundee | DS | 1868 | 1 |

| 1868 | Wildfire | st | SS286 | Dundee | DS | 1860-8 | 9 |

| 1869 | Alexander (3) | st | SS016 | Dundee | DS | 1864-9 | 6 |

| 1874 | Arctic (2) | st | SS024 | Dundee | DS | 1867-74 | 8 |

| 1874 | Tay (3) | st | SS261 | Dundee | DS | 1858-74 | 18 |

| 1878 | Camperdown | st | SS043 | Dundee | DS | 1860-78 | 19 |

| 1879 | Our Queen | st | SS194 | Dundee | DS | 1879 | 1 |

| 1879 | Ravenscraig | st | SS225 | Dundee | DS | 1866-79 | 14 |

| 1880 | Xanthus | s | SS291 | Peterhead | DS | 1852-80 | 27 |

| 1881 | Victor | st | SS282 | Dundee | DS | 1848-81 | 34 |

| 1882 | Jan Mayen (1) | st | SS135 | Dundee | EG | 1860-82 | 23 |

| 1883 | Mazinthen | st | SS176 | Dundee | DS | 1851-83 | 33 |

| 1884 | Narwhal | st | SS183 | Dundee | DG | 1859-84 | 26 |

| 1885 | Cornwallis | st | SS055 | Dundee | DS | 1884-5 | 2 |

| 1885 | Intrepid | st | SS130 | Dundee | EG | 1852-85 | 34 |

| 1886 | Catherine | s | SS044 | Peterhead | DS | 1883-6 | 4 |

| 1886 | Jan Mayen (2) | st | SS136 | Dundee | DS | 1875-86 | 12 |

| 1886 | Resolute | st | SS227 | Dundee | NL | 1880-6 | 7 |

| 1886 | Star | st | SS253 | Dundee | DS | 1883-6 | 4 |

| 1886 | Triune | st | SS276 | Dundee | DS | 1884-6 | 3 |

| 1887 | Arctic (3) | st | SS025 | Dundee | DS | 1875-87 | 13 |

| 1892 | Chieftain (2) | st | SS046 | Dundee | EG | 1884-92 | 9 |

| 1892 | Maud | st | SS175 | Dundee | DS | 1884-92 | 9 |

| 1899 | Polar Star | st | SS205 | Dundee | CG | 1857-99 | 38 |

| 1902 | Nova Zembla | st | SS190 | Dundee | DS | 1875-1902 | 28 |

| 1903 | Vega | st | SS281 | Dundee | DS | 1903 | 1 |

| 1907 | Windward | st | SS290 | Dundee | DS | 1904-07 | 4 |

| 1909 | Snowdrop | s | SS245 | Dundee | DS | 1905-08 | 3 |

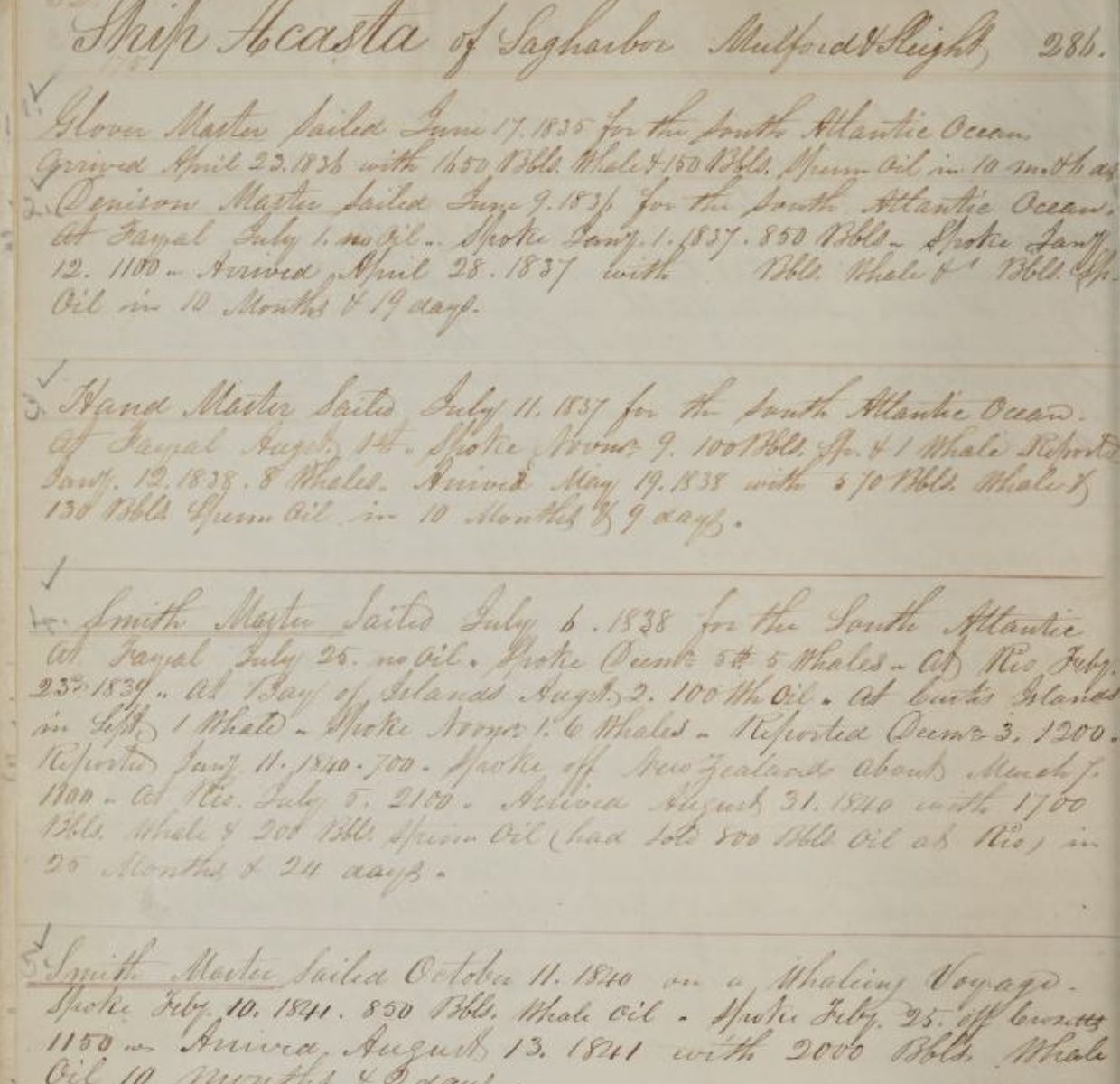

Dennis Wood Abstracts now searchable

Dennis Wood Abstracts of Whaling Voyages are brief handwritten summaries of whaling voyages–including vessel, owner & master; departure & arrival dates; reports during the voyage; oil & bone catch; and events of the voyage–compiled over more than forty years (1830–1874) by Dennis Wood, a merchant and whaling agent in New Bedford, and a director of the Mutual Marine Insurance Company. The abstracts were drawn from news reported in the Whalemen’s Shipping List and Merchants’ Transcript, and from letters, telegrams, and reports brought back by vessels.

The New Bedford Free Public Library has scanned the four volumes from its collection, containing more than 2,300 pages, and placed them on the Internet Archive. Judith Lund has updated 6,700 voyage records in the American Offshore Whaling Voyages database with volume and page references to the Abstracts, and WhalingHistory.org now provides links directly to pages in the scanned volumes.

All searches on WhalingHistory.org will now return references and links to relevant Dennis Wood abstracts, just as they provide links to crew lists and scanned log books. Or, you may search only within the Abstracts by selecting “Dennis Wood Abstracts of Whaling Voyages” from the “Explore” dropdown menu in the header of any page.

American and British Southern whaling data updated, 2021

The American Offshore Whaling database has been updated for 2021, adding more than 370 voyages as well as many corrections and updates to existing voyage entries. The added voyages are primarily from the 18th century, extracted from local newspapers.

The British Southern Whale Fishery databases have been thoroughly revised and updated with additional voyages, crew lists, and data corrections.

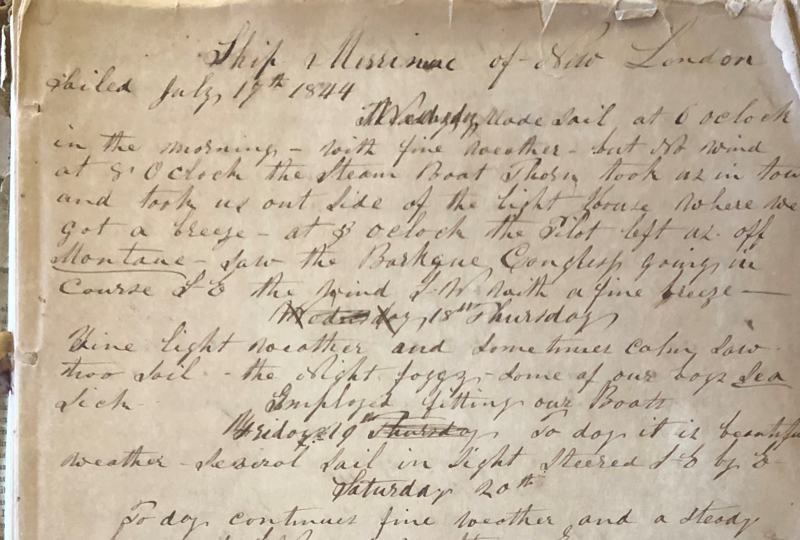

The Merrimac Journal Transcription Project

When the Journal arrived at the Custom House in August 2020, it was examined by Susan Tamulevich, Executive Director, and Laurie Deredita, librarian, who noted its fragile condition. Despite the temptation to start reading it, they decided that it would be prudent to handle the manuscript as little as possible. After an article appeared in the Day of New London, it became clear that there was a lot of local interest in this New London-based whaling journal and that it would be useful to have a transcription of the pages publicly available. To this end, Susan took photographs of each of the pages so that a transcriber could work from the images rather than the pages themselves. Eventually, it was decided to “crowdsource” the task of transcribing to volunteer “scriveners.” With the Custom House closed during the COVID-19 pandemic, it seemed like the perfect project for people interested in maritime history but stuck at home. All of the sending, receiving and editing of documents would take place electronically.

Susan’s call for volunteers received local and national media attention and she was nearly overwhelmed with responses from people all over the country and abroad who wanted to try their hand at transcribing. In early January 2021 she began to send out the page assignments and instructions to the volunteers. Within days, Laurie started receiving the completed transcriptions from the volunteers and she began to post the texts, side-by-side with the corresponding photographed pages from the manuscript, on an online website called Voyage of the Whaler Merrimac, created on the Omeka platform. By February 2021 the transcription part of the project was complete but the editing process took another two months until we decided that it was good enough.

-

- Read the Merrimac journal →

- Learn about the 1844–47 voyage of the Merrimac on WhalingHistory.org →

- Learn about the 1851-54 voyage of the General Williams on WhalingHistory.org →

- Visit the New London Maritime Society Custom House Maritime Museum →

Agent/Owner data added to American Whaling Voyages

Agent/Owner entries have been added or updated for more than eight thousand American Offshore Whaling voyages. Now there are agent/owner entries for more than two-thirds of the fifteen thousand voyages in the database.

This makes it possible to view the voyages credited to a single agent/owner together in search results. For example, view the voyages of the Warren, Rhode Island whaling merchants Driscoll & Child at https://whalinghistory.org/wri/AA0400.

The usual guidelines for searching names also apply here. There really were multiple people with similar names, the same person did sometimes vary the way he spelled his name during his lifetime, and firms and partnerships changed over time. But also, historical records were not always precise, clerks sometimes misspelled, and two hundred year old handwriting can be difficult to read. As a result sometimes you will find multiple, slightly different entries for what may or may not be the same merchants. To see an example, search “Driscoll & Child” and notice the variations. To make sure you find what you are looking for search thoroughly, explore variant spellings, and try the suggestions on our “Just Search” page.

American and British Southern whaling data updated

The American Offshore Whaling database has been updated, adding more than 3,500 crew list entries for 155 voyages as well as many corrections and updates to existing voyage entries.

The British Southern Whale Fishery database has been updated with additional voyages and data corrections.

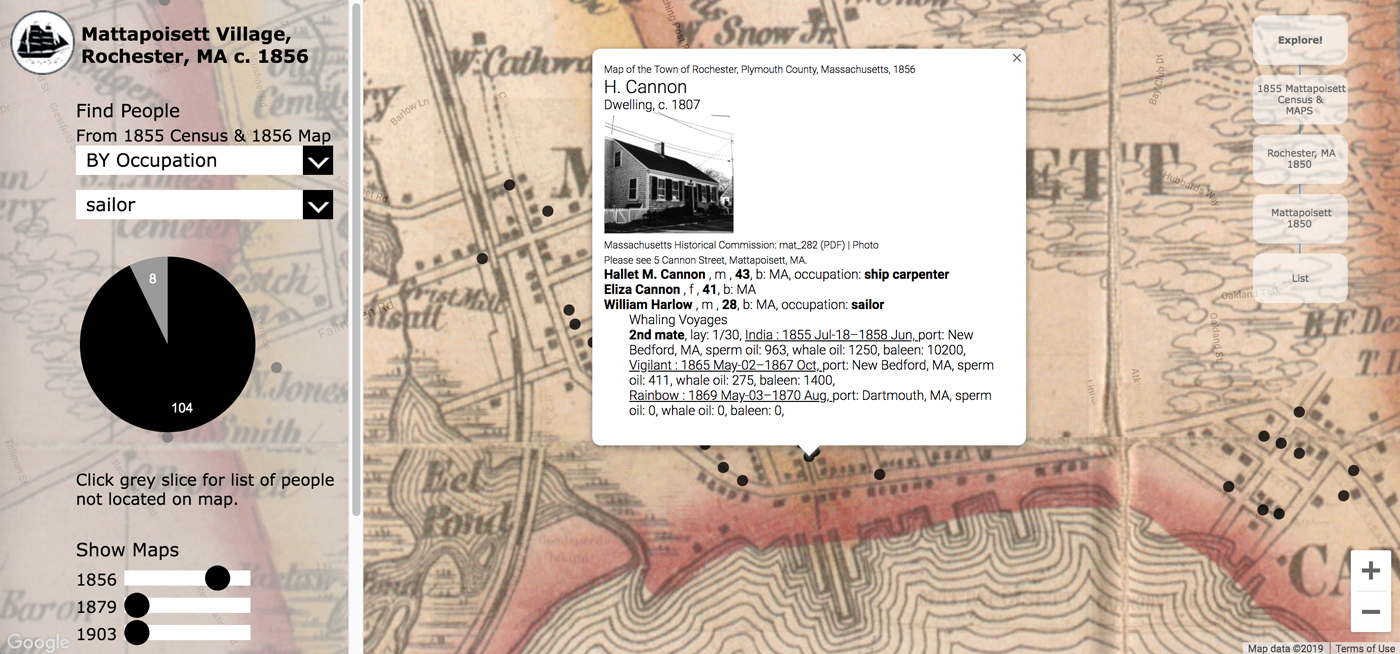

Mattapoisett Data Stories

Through interactive maps and visualizations, Mattapoisett Data Stories invites exploration of life in the shipbuilding village of Mattapoisett, Massachusetts, in the late 1700s and mid-1800s by integrating map, census, and American Offshore Whaling Voyages data.

Explore Mattapoisett Data Stories →

Through an interactive map focusing on village residents, visitors can explore Mattapoisett village c. 1855/1856. Clicking on the map reveals information about the residents, the whaling voyages residents crewed, historic buildings, and related Mattapoisett Museum collection records. Overlaying later town maps shows how the town changed between 1856 and 1903.

Visualizations summarize the growth of the U.S. whaling and Mattapoisett shipbuilding industries during the 1800s, document changes in occupations, and provide contextualized access to collection images.

The underlying microdata may be viewed online and downloaded.

Mattapoisett Museum: 2014, 2019

New Features and New Data added to WhalingHistory.org

WhalingHistory.org has been greatly expanded in the past year to include whaling data from more countries, links to scanned documents online, and a new global search.

New Data

- British North American (BNA). A database of whaling voyage data has been added. This includes information on 170 masters, 84 vessels and almost 300 whaling voyages from the east coast of British North America from 1779 through 1845 The details of these voyages are largely the work of Andrea Kirkpatrick, compiled for her forthcoming book on this fishery.

- Les Baleiniers Français (LBF). Almost 1,000 records for French whaling voyages come primarily from digitization of Thierry DuPasquier’s tables from his two books documenting that country’s whaling trade. The data was confirmed and augmented by the generous contributions of Peter Tremewan who shared his translations of French maritime documents from the Archives Nationales, in Paris.

- American Offshore Whaling Voyages (AOWV). The data already on WhalingHistory.org has been edited and augmented with new biographical information about whaling masters and their wives. And, crew lists for another 350 voyages have been added by a volunteer project at New Bedford Whaling Museum.

- British Southern Whale Fishery (BSWF). The voyage and crew list databases have been extensively revised and updated.

New Search

- Global Search. A new search page makes it possible to search all of the databases on WhalingHistory.org at the same time. Now that we have five major data collections, each with multiple datasets, global search is the most powerful way to start your exploration of Whaling History. Search for a name to find every occurrence—as a whaling master, crew member, owner, agent, master’s wife, vessel, … —in any database on the site.

- Advanced Search. Each database has a data viewer—a tabular display window to interact with the data—for precision searching and access to every data field available. Researchers can search, sort, and select subsets of the data for printing, copying to spreadsheets or other documents, and downloading.

New Access to Voyage Maps

Whaling History has from its beginning displayed maps of more than 1,300 whaling voyages based on data from the American Offshore Whaling Logbook database. Maps are included in the new Global Search, making them easier to locate. Browse voyage maps →

New Connections

- Many vessels and masters sailed from more than one country. Considerable work has gone into connecting our databases to each other. Global searches will find these linkages among the American, French and British North American databases. For example:

- French whaling masters who also sailed as American masters. View the list →

- British N. American vessels who also sailed from American ports. View the list →

New Scanned Documents

- Logbooks. Several hundred logbooks from whaling voyages are available for reading online. Read scanned logbooks →

- Sources. Source entries now include links to view the original source documents when they are available online. Browse scanned sources →

New Explore Menu

We have added an Explore menu to offer new ways to dig into the Whaling History databases and to feature aspects of the data that might not otherwise be discovered. One of the first Explore topics is Women who went whaling, an opportunity to find voyages on which the master’s wife sailed.